The following article, by Alan Littell, appeared in a recent issue of The Alfred Sun; it is reproduced here with his permission. Additional issues of The Alfred Student are available in Alfred University’s institutional repository, AURA (Alfred University Research and Archives). Managed by the libraries, AURA collects, distributes and preserves research and scholarship created by faculty, staff and students, as well as documents of historical or archival significance.

Ruminations on Local History: Alfred and its University, 1876

I recently stumbled on a curious publication. Housed in the archives of Alfred University and dated October 1876, the document—The Alfred Student—is a hodgepodge of essays, exhortations, biblical allusions and paid advertisements. It has less the look of a campus newspaper, more of a literary magazine and journal of cultural and political opinion.

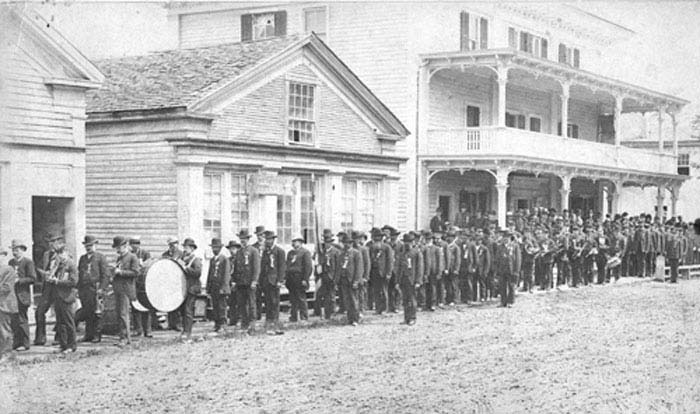

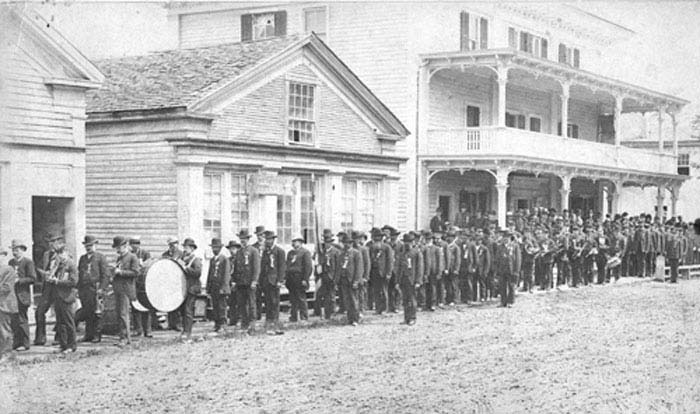

In an image dating from the 1880s, Civil War veterans gather for Memorial Day parade on Alfred’s Main Street.

The Civil War was of recent memory. The American commonwealth found itself in the grip of novel societal forces as emancipated slaves migrated north and west. A progressive Republican from Ohio, Rutherford B. Hayes, trailed in the run for the presidency (he would win after a disputed Electoral College vote).

The Alfred Student was a sometimes sensitive, sometimes amusing mirror of its time, of its university and of the remote rural backwater, called Alfred Centre, where it was written, edited and set in type. To get some idea of how people had actually lived in this particular place and age, we turn to the paper’s ads.

The range of goods and services then available included at least one that would be impossible to find locally today—the repair of mechanical clocks and watches. But in 1876, a Main Street jeweler named Amos Shaw guaranteed that his corrective surgery on weight- or spring-driven timepieces would be “done in the best manner.” Nearby, a variety store operated by a certain Silas Burdick advertised itself an embryonic Walmart. It sold books, shoes, wallpaper, lamps, toys, candy and drugs.

Alfred and its university in the mid 1870s. White building in foreground is the Burdick Hotel. Dome of Alfred University’s first astronomical observatory and the school’s Greek-revival chapel—now the admissions office (Alumni Hall)—can be seen in the middle distance.

There were many Burdicks living at the time in Alfred, and a hotel proprietor of that name offered “good accommodations for both man and beast, terms reasonable.” The Williams & Titsworth emporium, “over Coon’s Book Store, Alfred Centre,” sold white shirts for $1, while Mrs. E.J. Potter, dealer in “Millinery and Ladies’ Furnishing Goods,” on University Street, urged students and residents to “please call and examine.” And in a village in which outhouses accounted for sanitary arrangements and wells for water, Burdick & Green’s Hardware Store, on Main Street, stocked a supply of “eavetroughs” (roof gutters) to “furnish cisterns with good soft water” while protecting “walls from being thrown down by water freezing against them, which is a source of great annoyance.”

In its editorial columns,

The Alfred Student’s lead article extolled Alfred University’s pioneering support for the cause of coeducational schooling. The piece argued that instead of “shutting [a girl] apart” or by teaching a boy that “rudeness and selfishness are manly qualities,” joining them in the common enterprise of education resulted in “natural diversity and a richer character—a quick perception of mutual proprieties, delicate attention to manly and womanly habits…a higher and purer tone of morality.”

Elsewhere, the paper urged adoption of the metric system of measurement. We’re told also that Dartmouth College had raised its tuition and that one of its faculty members, a Professor Dimond, “died of brain disease.” At Alfred University, meanwhile, instruction was reported to be available in classical, scientific and teachers’ courses as well as in theology, the school having been founded by the breakaway sect of New England Baptists who observed Saturday, rather than Sunday, as the biblically enjoined day of rest and worship. Also offered was course work in industrial mechanics and in the leading communications wonder of the era, telegraphy.

The paper noted that tuition and “incidentals” came to $11 for each of the year’s three academic terms: fall, winter and spring. Board was priced at $30 to $40, room $3 to $6. The school assessed students $3 to $6 for “fuel” and $2 to $3 for “washing.” Mention was made that “rooms for ladies are furnished and carpeted” and that off-campus housing could be obtained from private families

One item jarred. It ran under the heading “Plain Language Concerning a Recent Unpleasantness.” A casual yet singularly stupid buffoonery of rhymed couplets, blatantly racist in idiom and tone, the piece had been reprinted—without critical comment or disclaimer—from Princeton’s student newspaper,

The Princetonian.

It later surfaced in another college publication, The Chronicle of the University of Michigan, as “the song of five juniors at Princeton who objected to having a colored man sit behind them in class.

What was so surprising about the item is that Alfred University and its Seventh Day Baptist founders had been in the forefront of agitation for ending slavery. The radical abolitionists Ralph Waldo Emerson and Frederick Douglass had lectured at the school. Before and during the Civil War, local church members, historically associated with the cause of emancipation, aided runaway slaves escaping to Canada on the so-called “underground railroad.” And in the spring of 1861, the nine male members of Alfred’s senior class heeded President Lincoln’s call for volunteers to fight for restoration of the Union. Moved by patriotism and religious fervor, they enlisted in two of the infantry regiments then forming in New York

In their classic survey, “The Growth of the American Republic

,” historians Samuel Eliot Morison and Henry Steele Commager contended that Lincoln’s 1863 Emancipation Proclamation had been “potentially more revolutionary in human relations than any event in American history since 1776.” The authors went on to say that the document had, in a very real sense, “lifted the Civil War to the dignity of a crusade.”

Yet make no mistake. Emancipation may have ended slavery; it did not end the racism that grew out of slavery in a national polity undergoing the strains of post-war reunification

“Lincoln’s own state of Illinois barred newly freed slaves from settling [there] in 1863,” notes Gary Ostrower, professor of history at today’s Alfred University

“I’d be surprised,” he added, “if some Alfredians…were not influenced by popular racist attitudes during the post-war years.”

– Alan Littell

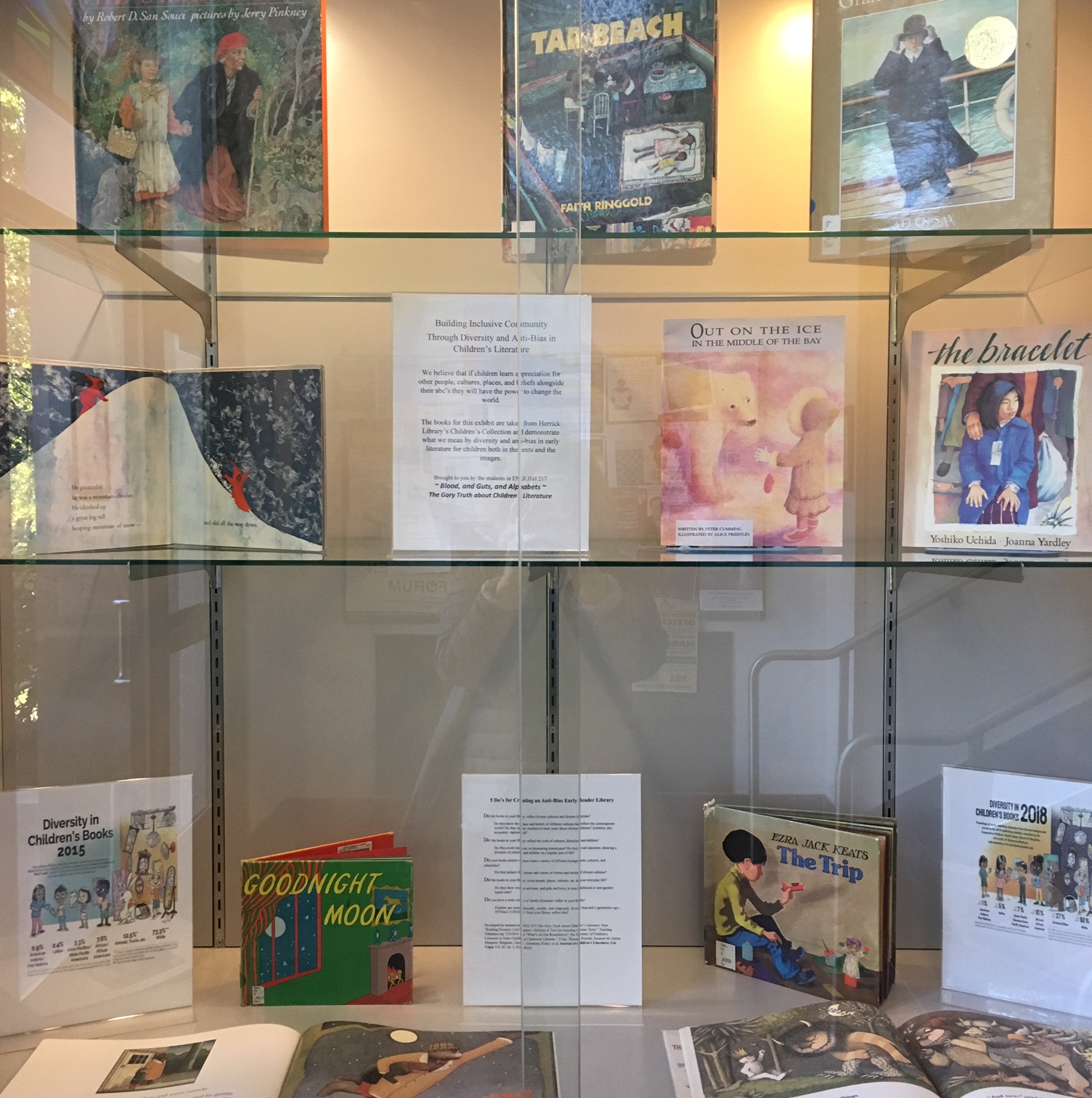

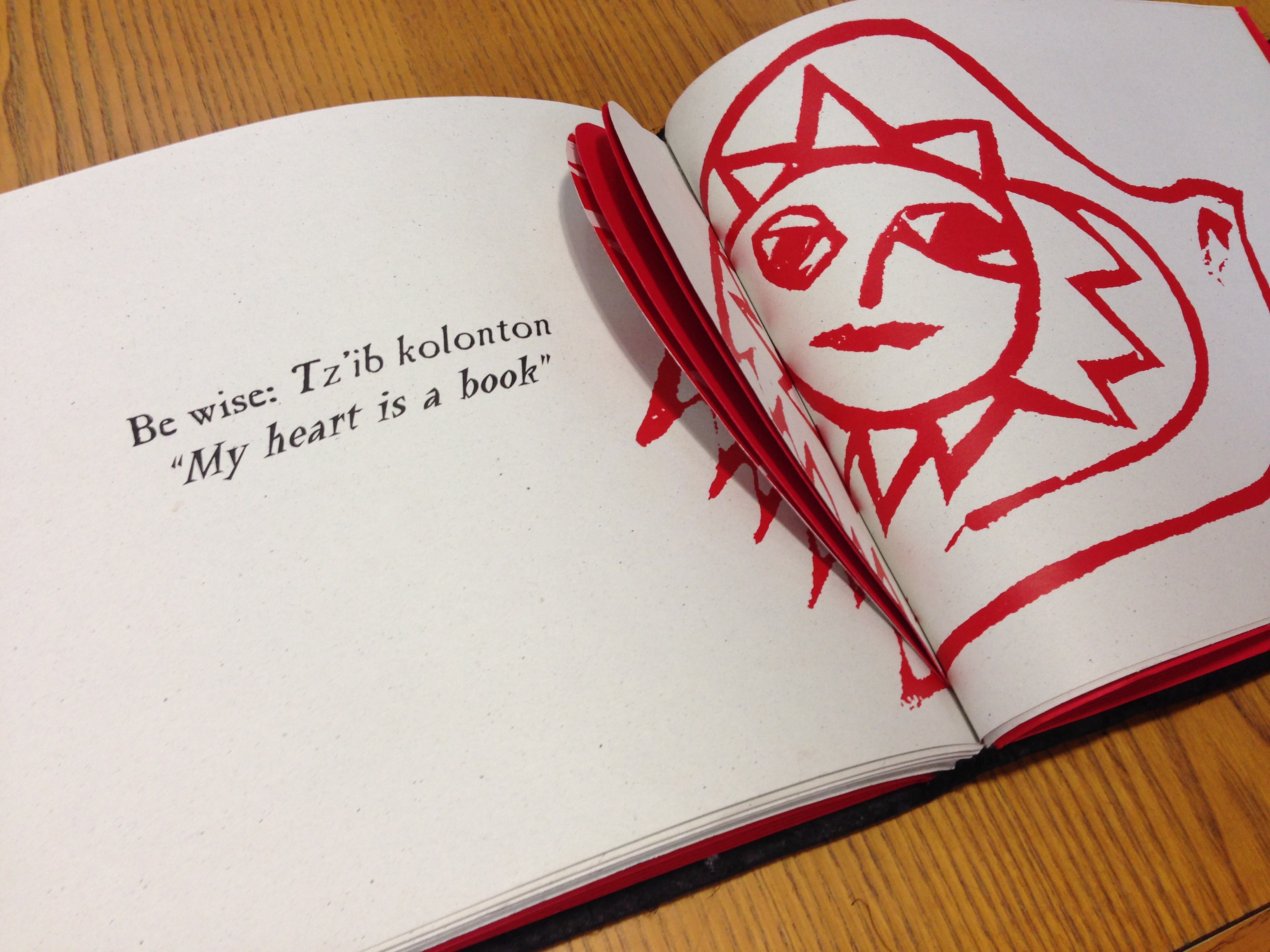

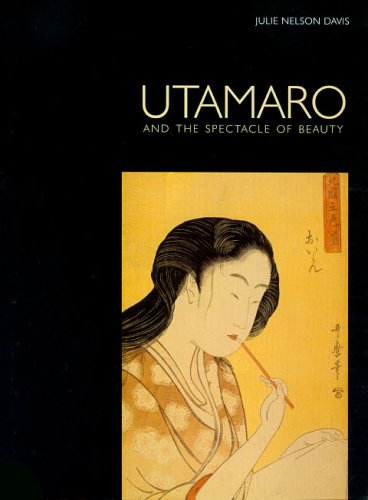

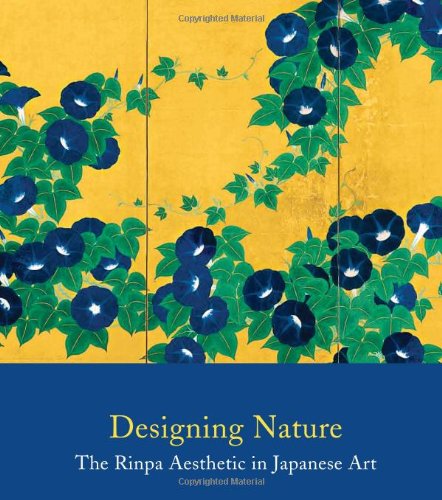

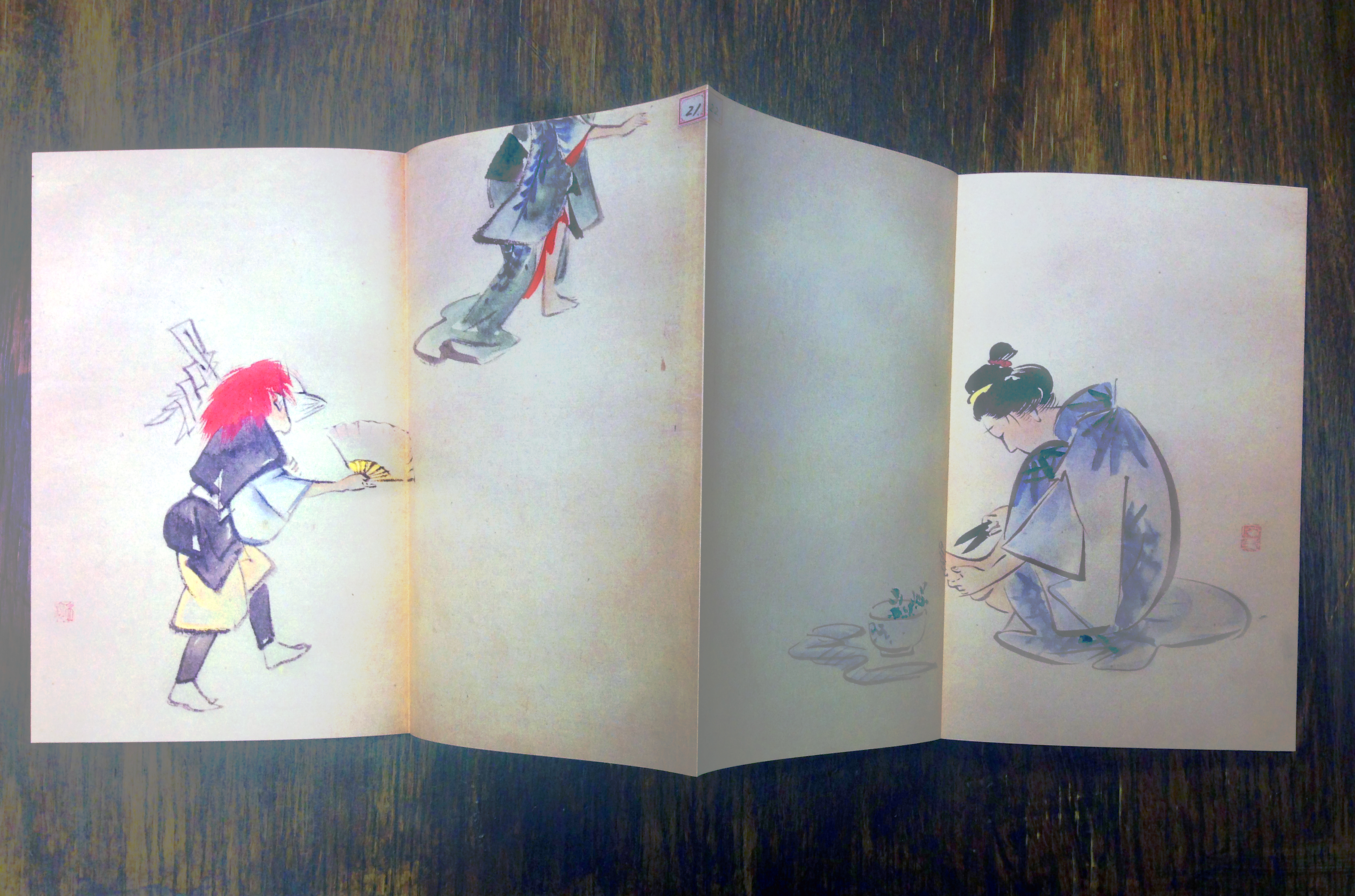

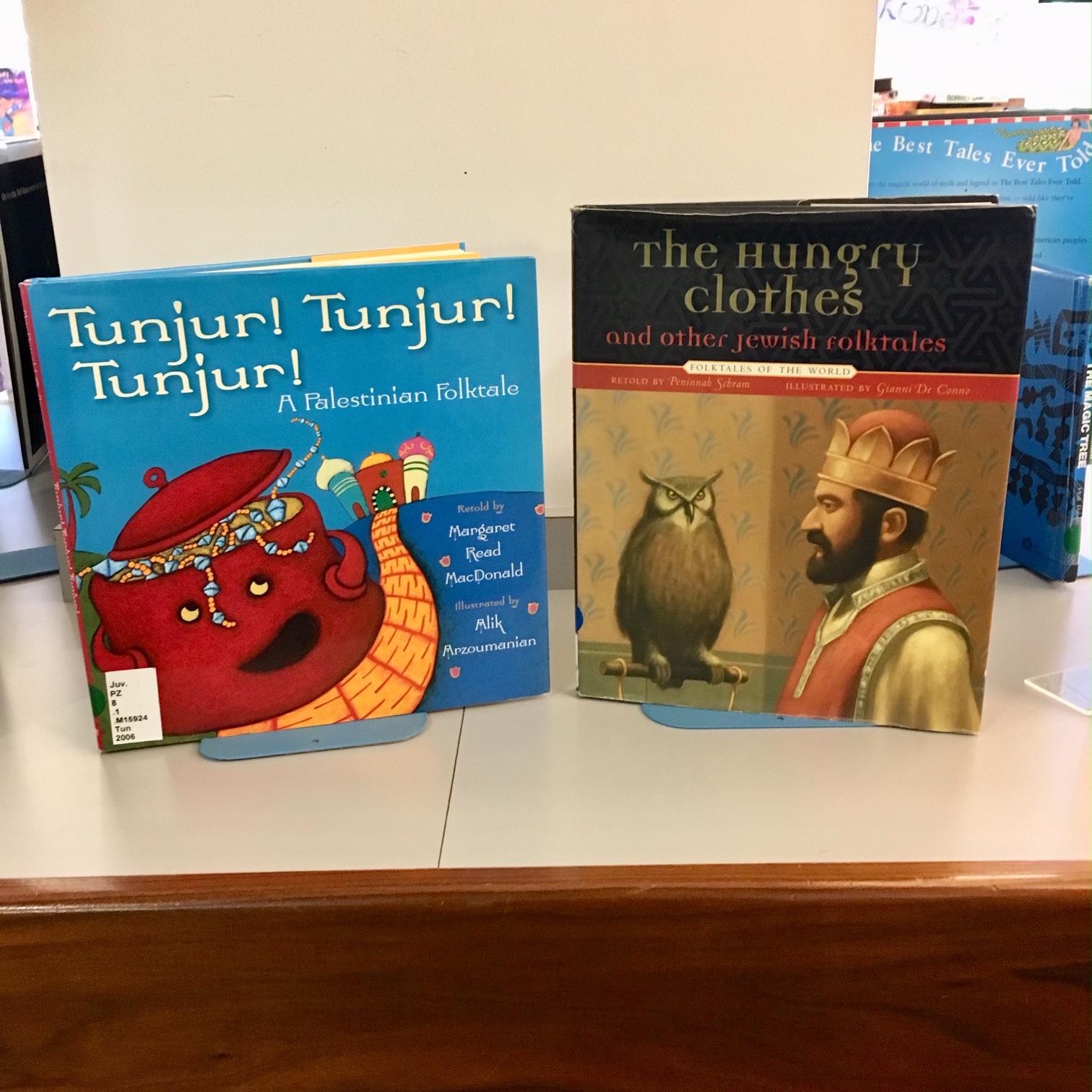

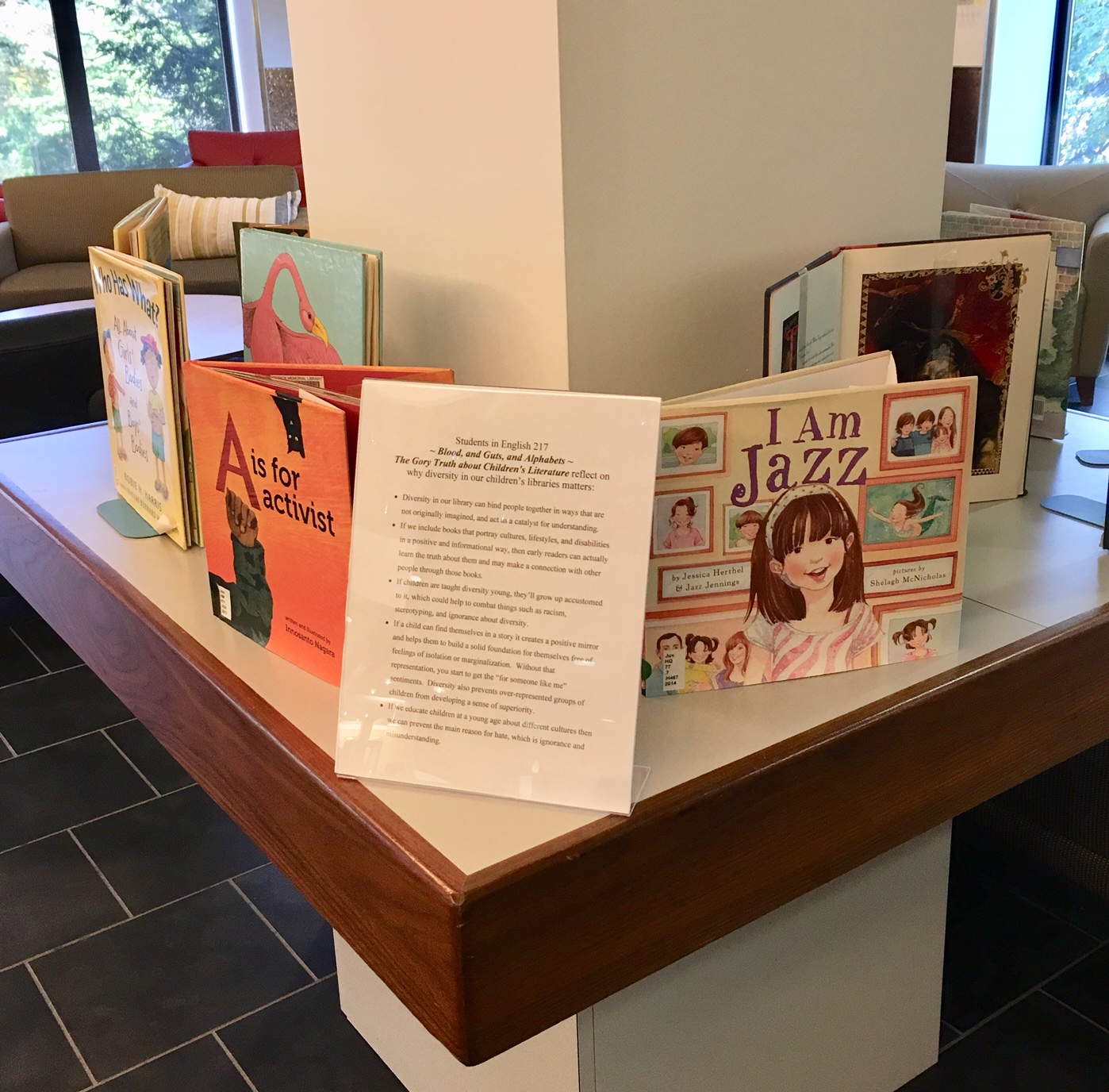

The exhibit includes books from Herrick Library’s Children’s Collection, selected for their demonstration (in both text and images) of diversity and anti-bias in early literature for children.

The exhibit includes books from Herrick Library’s Children’s Collection, selected for their demonstration (in both text and images) of diversity and anti-bias in early literature for children. DO the books in your library reflect the truth of cultures, lifestyles, and abilities?

DO the books in your library reflect the truth of cultures, lifestyles, and abilities?