You’d expect a library of art and engineering to have many books about art, but what you might not expect–or be aware of–is that the Scholes Library also has a significant collection of books that ARE art. More commonly called “artists’ books,” these volumes are works of art in and of themselves, and often are not restricted to the typical book format.

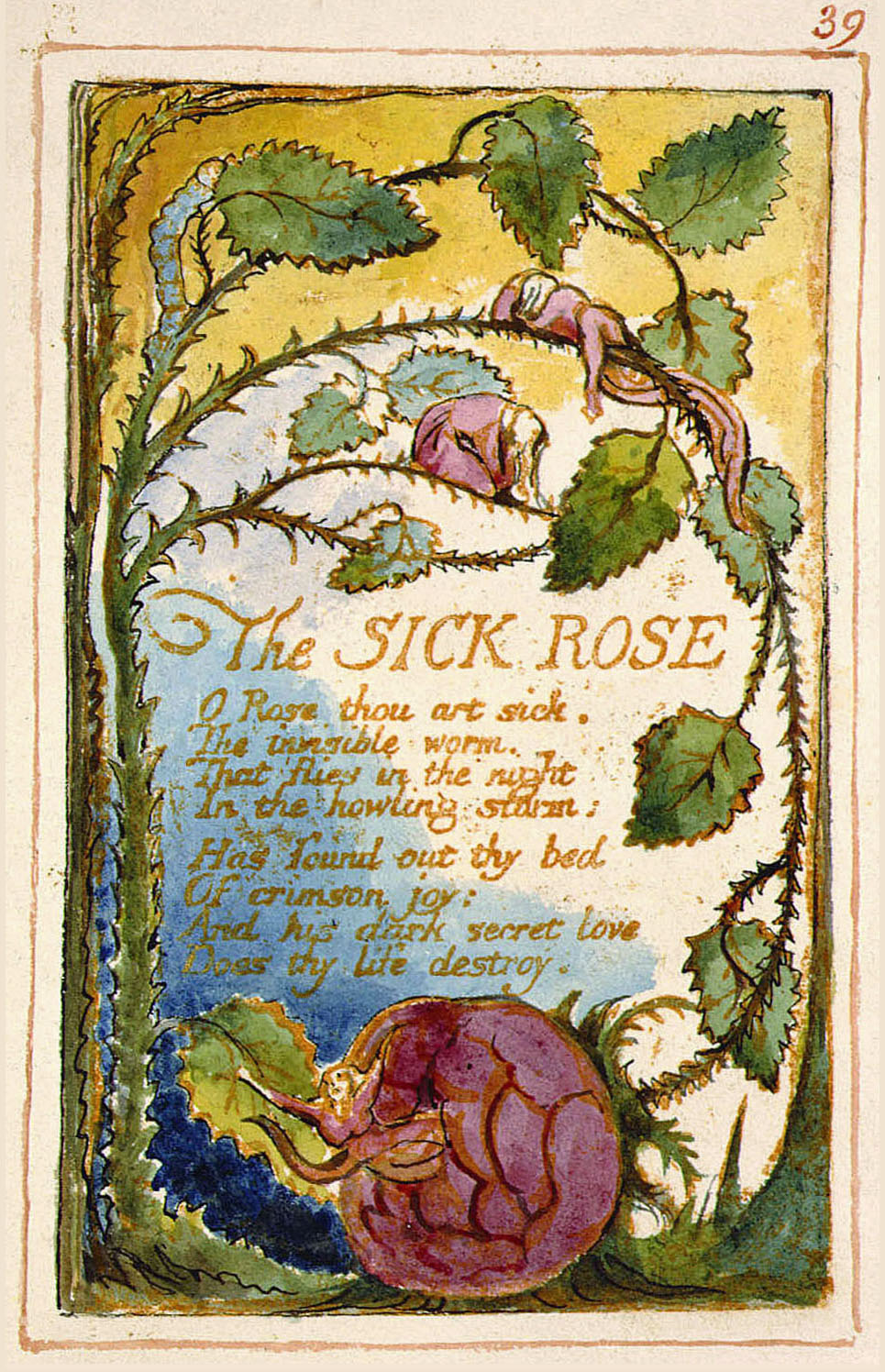

How you define the history and chronology of artists’ books depends largely on how you define artists’ books themselves. Illuminated manuscripts have existed for centuries, of course, some merging art and text in ways that would now be clearly recognized as belonging to the world of artists’ books. However, William Blake’s work in his Songs of Innocence and Experience is widely considered the most direct ancestor to the modern artist’s book. Unlike medieval illuminated manuscripts, which were generally highly collaborative, each copy of Songs of Innocence and Experience was written, printed, illustrated, and bound by Blake and his wife.

Some contemporary artists’ books could still be considered illustrated narratives or collections of poetry, like Blake’s work, but the majority do not present their content in such a linear fashion, or even draw such distinct lines between form and content. This may in part be due to the artist’s book’s strong historical connection to–and development from–the Dadaist movement, in which they took their place alongside performance art and published manifestos as a core part of the movement.

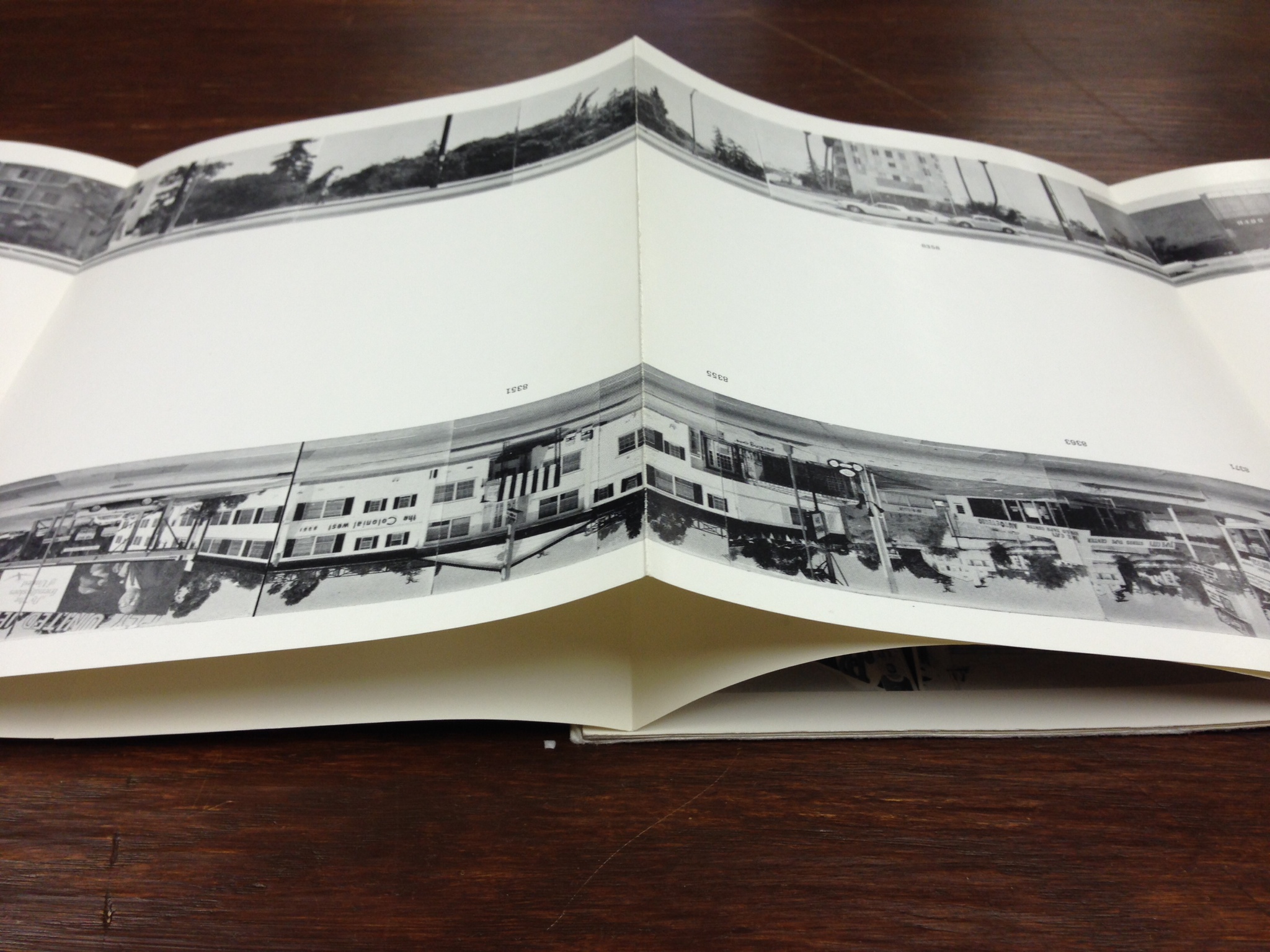

Every Building on the Sunset Strip, a Ruscha book in our collection that, according to the Getty’s “Pacific Standard Time” blog, “reinvented the artist’s book.”

The modern artist’s book, however–that is, the artist’s book as we know it today–can be in large part credited to the avant-garde and postmodern artists of the 50s, 60s, and 70s, most notably among them Dieter Roth and Ed Ruscha.

We happen to have significant collections of the works of both of these artists right here at the Scholes Library! A walk into our special collections room (after speaking with one of the librarians on duty) will reveal several works by Ruscha and Roth, including Ruscha’s Some Los Angeles Apartments and Roth’s Stupidogramme.

Ruscha’s work in particular plays with the format of the book, frequently expanding it into the accordion folds seen in Sunset Strip.

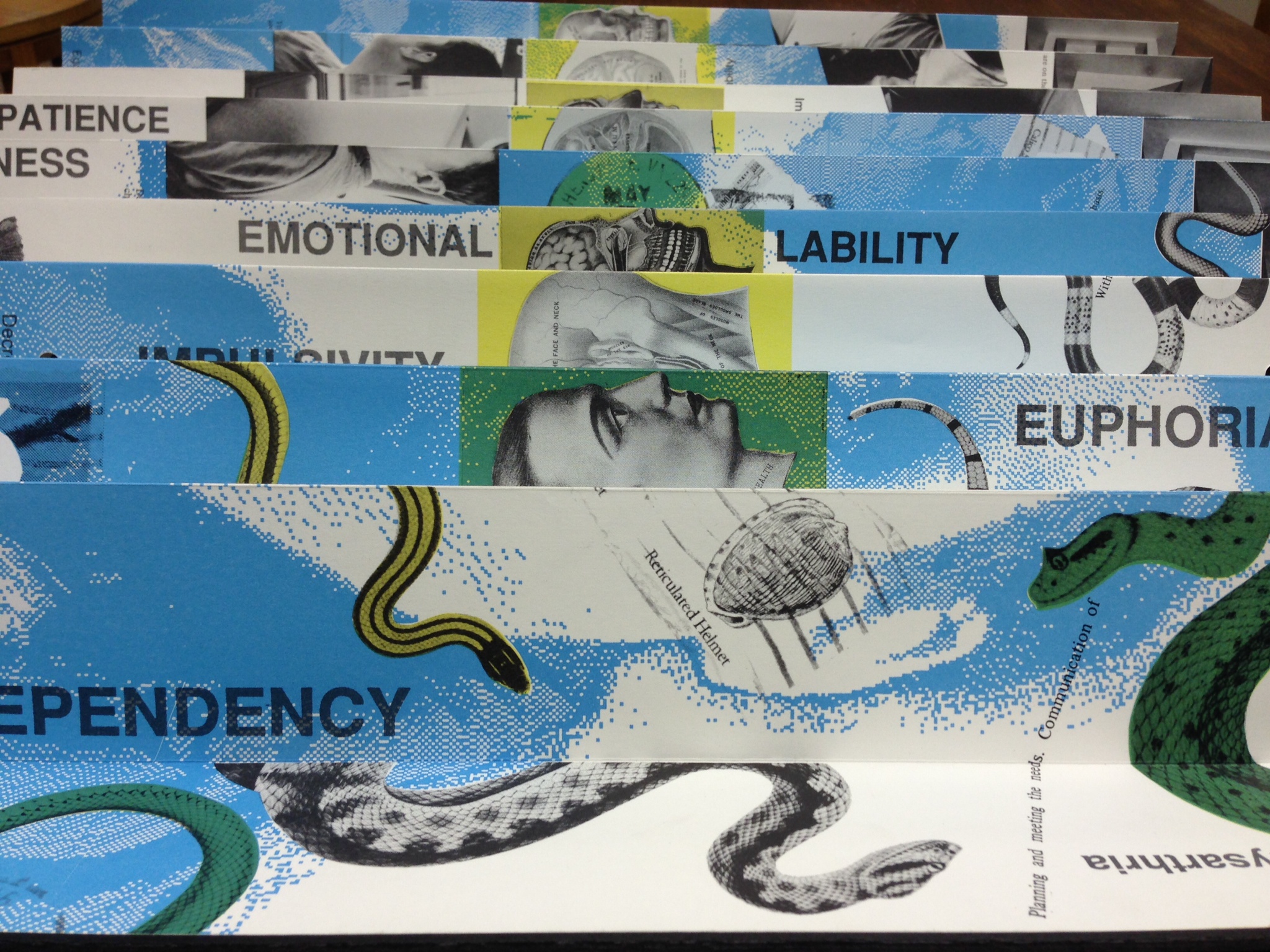

This alteration, denial, or subversion of the book form appears frequently in the works we have in our collection. The accordion fold, for instance, is crucial to the functioning of Scott McCarney’s Memory Loss. Printed on both sides and barely two inches wide when shut, Memory Loss reads differently depending on which angle you choose to view it from, seemingly orphaned words leaping across the folds of the paper to construct sentences along the length of the book.

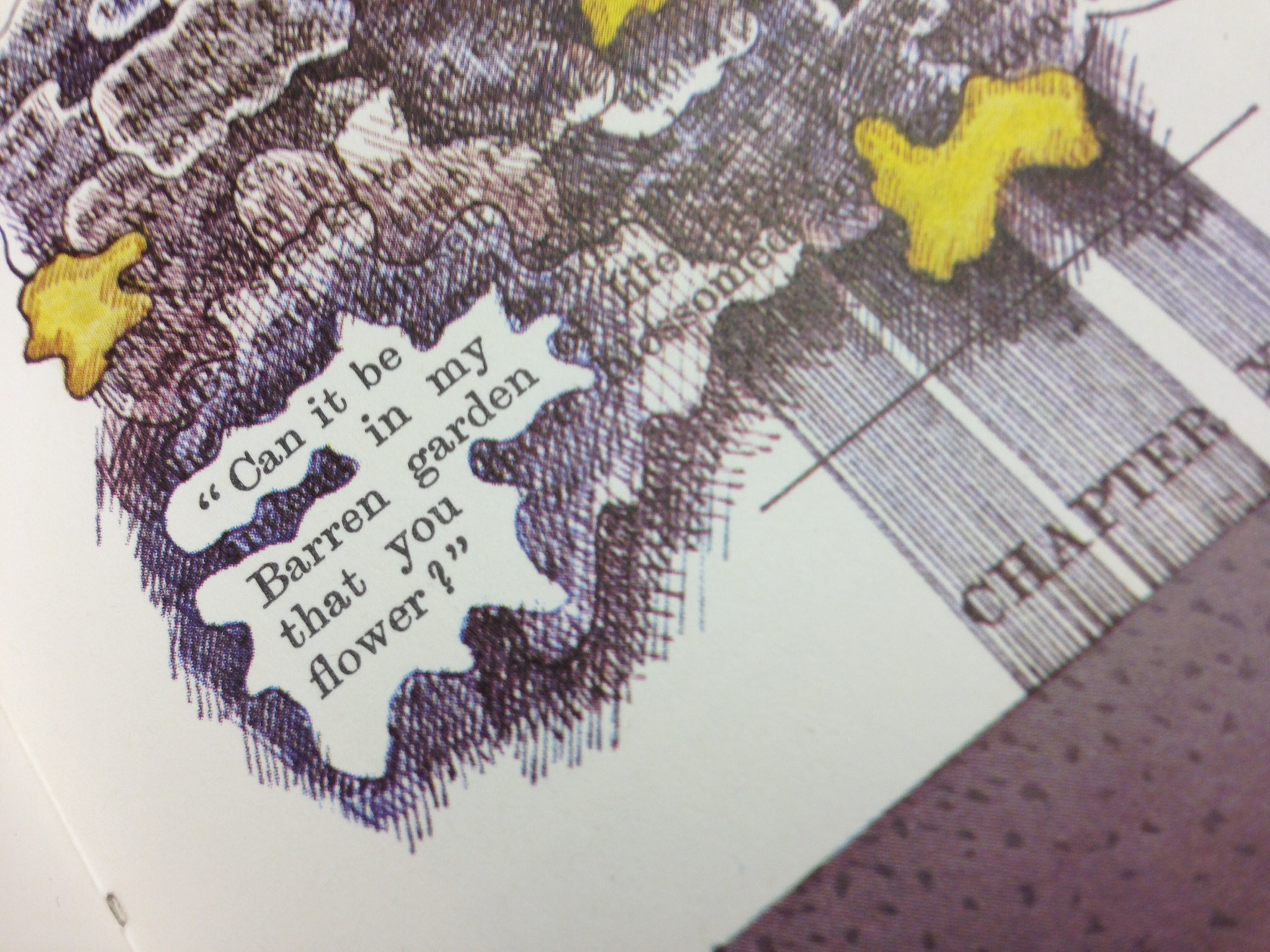

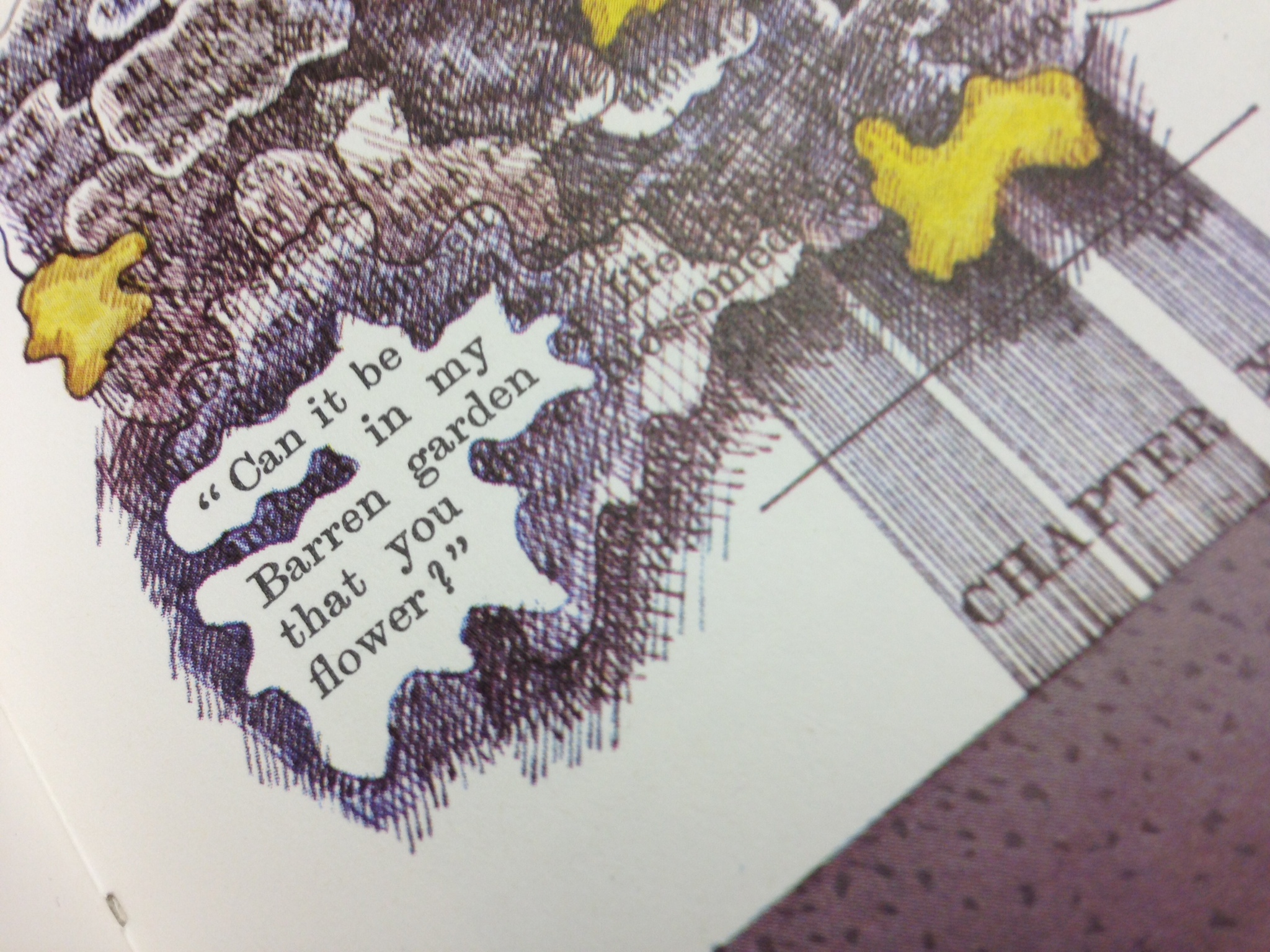

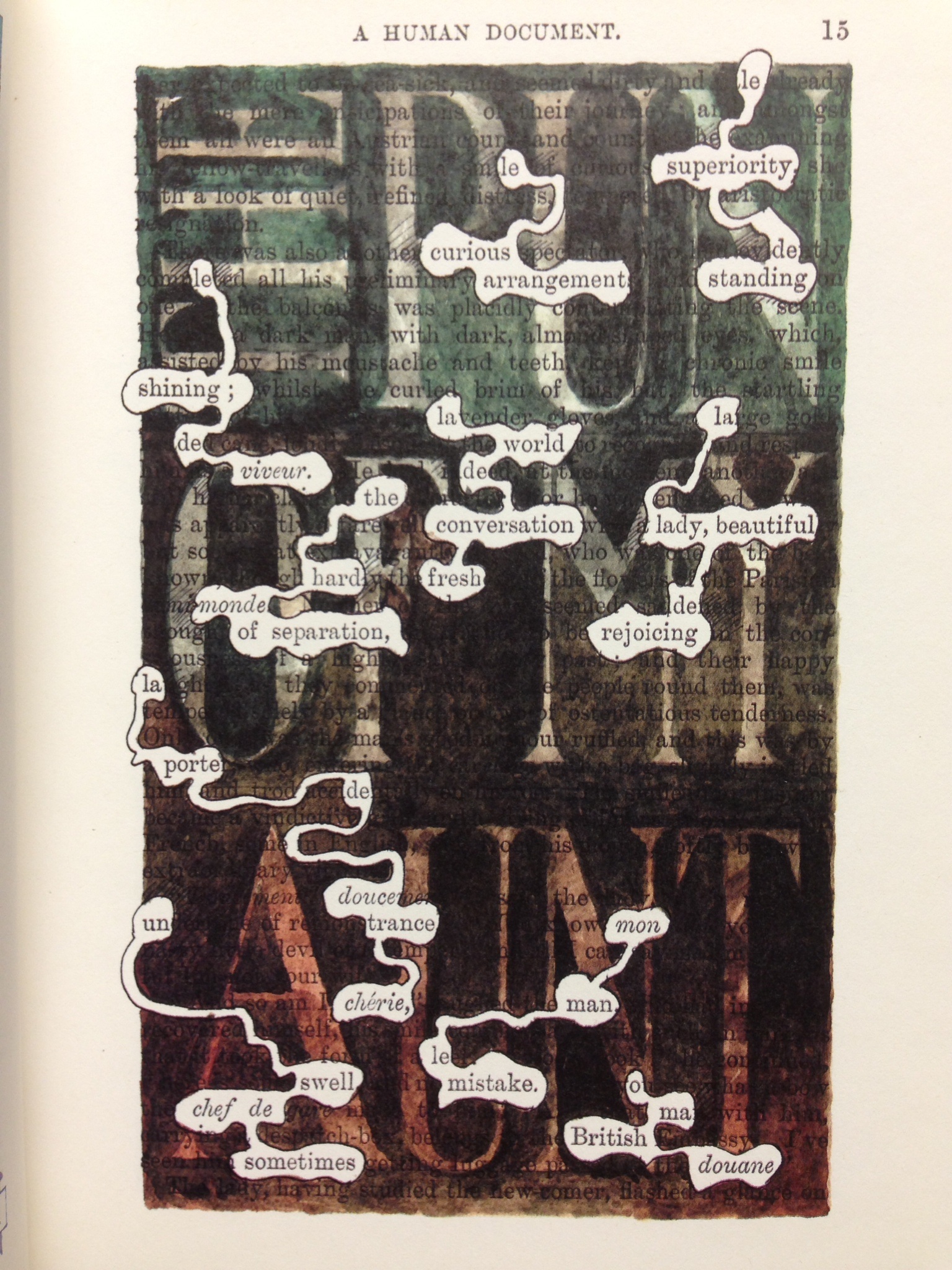

Still other works maintain the standard book form,

but use art to explore writing itself. In A Humument, Tom Philips took as his starting point an obscure Victorian novel by W.H. Mallock, A Human Document. By altering every page with painting and collage, he created an entirely new work, and brought out meanings from the text that the original author never would have intended–but which he nevertheless wrote.

but use art to explore writing itself. In A Humument, Tom Philips took as his starting point an obscure Victorian novel by W.H. Mallock, A Human Document. By altering every page with painting and collage, he created an entirely new work, and brought out meanings from the text that the original author never would have intended–but which he nevertheless wrote.If you’re interested in learning more about artists’ books, I’d also recommend checking out A Century of Artists’ Books. Written by Riva Castleman and published on the occasion of the MoMA exhibit of the same name, it is an excellent introduction to the art form. And, of course, feel free to search the Scholes collection for yourself!

-Eva Sclippa